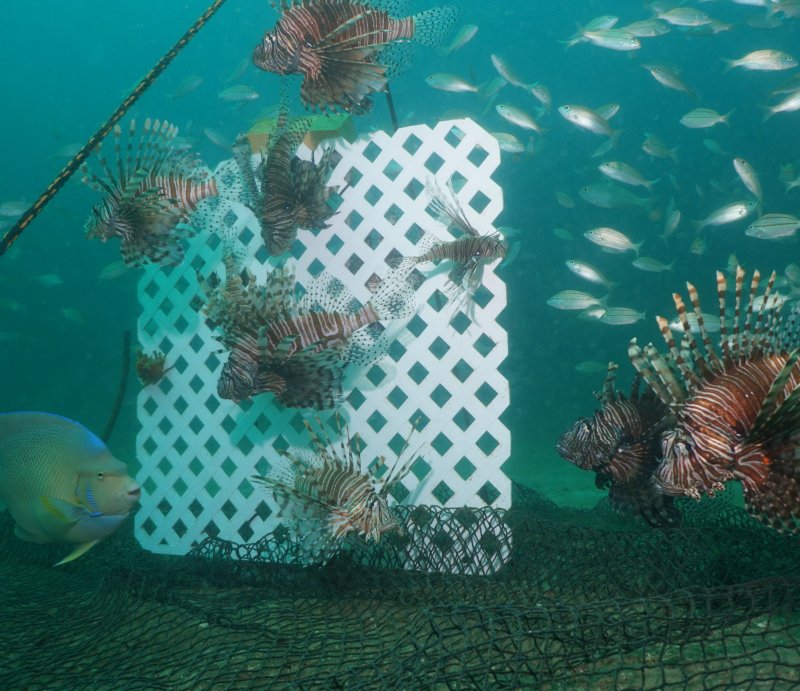

1 of 3 | Florida researchers recently found that a trap named after NOAA researcher Steve Gittings, was an effective and relatively safe trap to catch invasive lionfish in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo by Alex Fogg, courtesy of Okaloosa County

Aug. 26 (UPI) -- A new trap for invasive lionfish works so well that scientists believe it might help control the intruder that eats native fish and shrimp in Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, according to a study published Wednesday by the journal PLoS One.

The so-called Gittings trap, named for its inventor, can be deployed deeper than spear fishermen who currently provide most lionfish control, allowing it to catch lionfish abundant at those depths.

It also could provide a more regular supply of lionfish, which would encourage more restaurants and retail chains to sell the spiny sea creatures.

One national grocery chain, Whole Foods Market, features a page on its website called "Get to Know the Lionfish." Recipe suggestions include grilling it with herbs and lemon, baking with a bread crumb coating or making into ceviche.

"In the ocean, we really haven't seen an invasive species problem of this magnitude before," said Steve Gittings, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who invented the trap about six years ago.

"The trap could provide a money-making opportunity for fishermen to sell the fish and remove a problem," Gittings said.

Researchers from the University of Florida and other agencies studied the Gittings trap and modified lobster traps for six months in 2018, analyzed their findings and wrote the new study, "Testing the efficacy of lionfish traps in the northern Gulf of Mexico."

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission funded the work with a $50,000 grant.

The traps showed promise, but need further testing before they can be distributed widely to ensure they don't catch other species and that they work properly in various environments at an affordable cost, the study said.

"Gittings traps appear suitable for future development and testing on deepwater natural reefs, which constitute greater than 90% of the region's reef habitat," according to the study.

A total of 327 lionfish visited the traps, which caught 141 of them, along with 29 other fish, the study said.

The Gittings trap uses no bait, but rather a structure that attracts lionfish. It lies on the seafloor with a circular bottom frame. When someone retrieves the trap, the frame rises, allowing net curtains to close quickly around the fish.

Since it only closes upon retrieval, Gittings believes any problems caused by lost traps would be minimal. The lack of bait minimizes attracting other species.

Work at NOAA and the university continues to look at other traps also, especially by modifying funnels on lobster traps, but a specially designed lionfish trap is desired to reduce impact on other reef species, Gittings said.

Scientists believe lionfish -- native to the Indian Ocean and South Pacific -- were released by aquarium owners in South Florida. They now have spread throughout the East Coast, the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, where they are found in dense populations.

Researchers recorded the first lionfish in the Western Atlantic near Fort Lauderdale, Fla., in 1985, but no other sightings occurred until 1992.

In 2000, the number of sightings "began to increase exponentially," according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Tens of thousands are believed to exist on many reefs now.

Biologists with NOAA describe lionfish as indiscriminate eaters, basically swallowing any creature that fits in their mouth. Lionfish can reach maturity in less than a year. Adult males are about 4 inches long; females are about 7 inches long. Adults can grow as big as 12 to 15 inches.

They have 18 venomous spines and reproduce year-round, with females capable of releasing 50,000 eggs every three days. That allows them to quickly outnumber native fish populations.

Spear fishing is generally successful to land large numbers of lionfish, but divers can descend to only about 130 feet without technical diving equipment, said Holden Harris, lead author of the study and a fisheries scientist with University of Florida.

"Lionfish density is abundant at those deeper depths, probably because there are no predators," Harris said. "Lionfish offer a possible new source of income for lobstermen and spear fishers. That would help to control their population on some reefs."

Issues that still need study include how the Gittings trap can collect smaller lionfish, which frequently escaped from it, and how native fish can be excluded from the traps, Harris said.

Not everyone is enamored of the lionfish traps, though.

Lobster traps already catch a lot of lionfish, said Bill Kelly, a fisherman and executive director of the Florida Keys Commercial Fishermen's Association.

"Lobster traps already catch 50,000 pounds of lionfish meat in a year, so why do we need a new type of trap?" Kelly asked. "The Gittings trap works, but we want to use lobster traps and we are working on getting approvals to use lobster traps all year long."

If the Gittings trap ultimately proves effective, is affordable and distributed widely, Kelly said, lobster fishermen probably would use it in the off-season.

"Lionfish eat juvenile snapper and grouper, and have wiped out the snapper and grouper populations in many areas, so we do want to reduce their numbers," he said.